Authors: Prof Dr Pieter Steyn and Prof Dr Brane Semolic

This article in PM World Journal Volume VI, Issue 3 March 2017 – http://pmworldjournal.net/article/collaboratism/

Globalisation has dominated economics and trade for decades. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines globalisation as: “the development of an increasingly integrated global economy marked especially by free trade, free flow of capital, and the tapping of cheaper foreign labour markets”. Many critics, including delegates attending the 2017 World Economic Forum event in Davos, Switzerland, are of opinion that globalisation has flat-lined and is now going into reverse (Levy, 2016). This trend started with the financial crisis in 2008, and, now with the prospect of Brexit and President Trump having assumed office in the United States, globalisation is distinctly in decline. Moreover, critics believe that the world has reached a turning point in the nature of capitalism, a view also expressed by Steyn and Semolic (2016). At the same time, protectionism is rising in popularity. In a note to clients, Jason Rotenberg and Jeff Amato (from Bridgewater, one of the world’s largest hedge funds) averred that the political backdrop in the world looks negative for globalisation and everything associated with it. Many critics believe that globalisation, competitiveness and internationalism are firmly in retreat, and that the protectionism now rearing its head does not augur well for the future. With the financial crisis of 2008 seen as the trigger of this phenomenon, many critics, including George Saravelos, chief foreign exchange strategist at Deutsche Bank, view the retreat as a new global mega-trend. Saravelos is of the opinion that globalisation has reached its peak and that the world is about to witness an unwinding of this trend, even labelling it as the slow death of globalisation.

Saravelos identifies three crucial aspects involved in the demise of globalisation. Firstly, he believes that world exports as a percentage of GDP peaked in 2014, having been in steady decline since then. Gross financial flows into the United States peaked in 2008 with the financial crisis, and are now moving sideways. Currently the number of new trade deals is at its lowest in more than two decades. Secondly, anti-globalisation sentiments are growing in the political domain. Brexit is set to be implemented in the foreseeable future, and the recent United States election was heavily focused on concerns related to globalisation and immigration, with other countries to follow. Thirdly, changes in regulation worldwide suggest that globalisation is waning. He mentions that China is slowing down on its capital account liberalisation programme, and changes in banking regulation have forced greater national reporting and capital standards, while raising the cost of cross-border business. The position of Deutsche Bank is that the only exception in the reversal of globalisation is the global dissemination of ideas, powered by political freedom and assisted by persistent innovations in technology, such as social networks.

Saravelos’ Deutsche Bank colleagues John Reid, Nick Burns and Sukanto Chanda, are of opinion that the current economic age is reaching its cul-de-sac. They believe that the global economy will change drastically over the decades to come, and that it will be subjected to subdued growth, lower profits, higher inflation, and diminishing global trade. Moreover, they argue that the world has reached a demographic peak and that huge changes will occur in the near future, predicting what they call “a far less exciting economy”. They contend that the deterioration will lead to a situation where it is unlikely that the next couple of decades will see real growth rates returning to the pre-crisis levels. They add, however, that should a sustainable exogenous boost to productivity surface, a more optimistic scenario may result, but they find it hard to see where such a boost will come from. Like many other critics, George Osborne, former British Chancellor of the Exchequer, believes that the forces of protectionism are increasing, and he is concerned that the pace of technology growth can be detrimental to economic well-being. The former vice chairman of Merrill Lynch Europe, Lord Adair Turner, is concerned that advances in technology are actually undermining capitalism, killing jobs, driving inequality and preventing the global economy from recovering from the financial crisis of 2008. He believes that the current capitalist system is not delivering as it should, and also not to

enough people to maintain its legitimacy. He labels this “tech-driven inequality that contributed to the popular resentment for elites and mainstream politics”, and calls for a solution to “the problems presented by the new tech economy” to restore global trust in capitalism and repair the global economy. At the recent 2017 World Economic Forum gathering in Davos Switzerland, the same sentiments as above were expressed, accompanied by major disagreement on what the solution should be. All admitted the failure of political and business elites to predict

any of the political events that occurred during 2016, and even raised questions regarding their capability to understand and to address the anti-establishment trends and events that emerged. However, all were in agreement that change for the better should occur. This group included two Nobel-laureate economists, Joseph Stiglitz and

Angus Deaton, who are very critical of the current European order.

In a discussion on “populist middle-class anger” screened by Bloomberg television, the opinions of heavyweight panellists, inter alia, International Monetary Fund managing director Christine Lagarde, Bridgewater’s founder Ray Dalio, and Harvard economics professor Lawrence Summers, differed widely. Lagarde proposed that policymakers

should implement measures such as fiscal and structural reforms to appease people who are disgruntled with the current situation. Summers suggested a three-point plan that includes: public investment in infrastructure, technology and education; making global integration work for ordinary people; and, finally, enabling working people

in terms of job security, education and home ownership. A solution on the type of structural reforms to introduce, or how to make global integration work for ordinary people that would lead to a better life for all, was not offered.

Saravelos’ observation of China slowing down on its capital account liberalisation programme, and tighter banking regulation forcing greater national reporting and capital standards while raising the cost of cross-border business, was alluded to earlier. Many critics refer to cheap labour in emerging markets being the driver of globalisation over

many decades, but warn that it is becoming more expensive by the year. The earliermentioned Bridgewater note specifically highlights that the rise in cost is particularly true in China, where a stronger currency and higher domestic labour costs are responsible for China’s share of global trade flattening. They also point out that the cost

advantage of building a factory in China versus locally has shrunk considerably. Consequently, it serves less purpose to move manufacturing assets to supposedly lowlabour-cost countries as time passes. The current authors moreover assert that for purposes of productivity, quality and competitiveness, modern manufacturing facilities are continuously reverting to more sophisticated process technology, and information and communication technology requiring higher-skilled workers. Workers who are more highly skilled are often more readily available in advanced local economies where a better education and training system exists than in emerging markets. Thus, the current authors contend that technological advancement should not lead to loss of jobs. On the contrary, as further discussed below, the appropriate use of technology is an integral part of a sustainable solution to the prevailing problematic situation.

Global Trends and the Dawn of the Fourth Industrial Revolution

It is clear that a solution to the current situation should be found sooner rather than later so as to prevent continuing meltdown of the world economic order. Peter Drucker reminds us: “Long-range planning does not deal with the future decisions, but with the future of present decisions.” Many experts and organisations are dealing with questions on how to anticipate the future and how to recognise and understand global and industrial trends and react on time. In 1998, the USA-based Trends Research Institute (Celente, 1998) already recognised the major changes and development trends that are shaping our lives today. These are, inter alia: digitalisation and its impact on increasing self-employment; industry reshaping; instability; and downsizing accompanied by work decentralisation that keeps more people at home (with possibilities of face-to-face interactive communication and participation globally). The Gartner Group (Pallot & Pawar,2005) already in the 1990s projected that by 2006

people would spend nearly 70% of their time working collaboratively through technology, and not necessarily face-to-face.

Moreover, futurists often equate advances in technology with advances in civilization (Celente, 1998). To exploit innovative technologies for the benefit of all stakeholders requires a profound understanding of how these novelties will affect personal and business lives, organisations in developed and less-developed countries, and how they

will reshape organisational landscapes, and societies and culture. It is vitally important to gain a holistic understanding of the risks involved and to plan appropriate solutions for the timely mitigation of the risk and associated complexity. This has hardly ever been done on time in the past, despite having had ample opportunity to critically peruse existing business models and to act to prepare and empower people for the looming threat of transformation and change. Unfortunately, organisations traditionally resist strategic organisational and behavioural transformation and change, often to their substantial detriment.

In 2014, PricewaterhouseCoopers declared (PwC Report, 2014) that the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which is characterised by increasing digitisation and interconnection of products, value chains and business models, has arrived. The researchers recognised that the globalised industrial environment was becoming increasingly complex, dynamic and high-tech, but that new enabling technologies were providing opportunities for the introduction of new market services and for upgrading existing products through innovative services and business models. It became clear that to achieve a competitive edge, organisations would need to focus on their key competencies and develop both technological and organisational excellence. It was evident that to survive, modern organisations were increasingly becoming an integral part of local, regional and global supply and value chains. Moreover, PricewaterhouseCoopers recognised that specialisation, improvements, and innovation supported by partnering are key elements of Fourth Industrial Revolution businesses. In an article published in the Harvard Business Review, Cross and Grant (Jan-Feb, 2016) aver that as business becomes increasingly global and cross-functional, the

vertical silos in organisations are breaking down, connectivity is increasing, and teamwork is seen as a key to organisational success. The results of their two decades of research indicated that the time spent by managers and employees in collaborative activities had increased by 50% or more. During that period of time, the current authors published an article in the PM World Journal of February, 2016, featuring their collaboratist business model of virtual networks of partners (Steyn & Semolic, 2016).

The above-mentioned phenomenon is what the current authors define as emerging “collaboratism”. The key competencies embedded in current enterprising supply and value chains, inter-organisational and interpersonal productivity, and the ability to permanently innovate, are the main challenges of emerging collaborative business

models. Coupled to this are knowledge and knowledge workers that are becoming key resources arguably more valuable than capital in the emerging knowledge-based collaboratist economy. The current authors observe that multi-organisational operations and development collaboration platforms, with an open innovation concept of work and philosophy are emerging. These collaboration platforms operate as virtual networks of local, regional, interregional and international supply and value chain business partners. The creation of virtual networks focusses firstly on engaging local and regional partner organisations to satisfy key competency needs, thus addressing the issue of the rise of protectionism. Extending the virtual network of partners internationally when competencies cannot be found locally or regionally, mitigates the decline of globalisation and establishes a

modern form of globalism. This constitutes what the current authors define as the emergent “collaboratist economy” or “collaboratism”.

The Collaboratist Business Model

The current authors agree with the proposals of Lagarde and Summers, and particularly support behavioural and structural reforms and making global integration work for ordinary people – these would benefit all stakeholders most. It is also imperative that serious attention be paid to investment in infrastructure, technology and education, since future economic success is profoundly dependent on particularly technological innovation and improved education. Moreover, while agreeing with the views on the decline of globalisation and rise of protectionism, the current authors disagree with the opinions expressed by critics regarding the negative effect and negative influence

of technological innovations.

It is submitted that the proposed collaboratist business model of virtual networks of partners is the sustainable boost to productivity that would mitigate the abovementioned fears expressed, and would turn the emerging economic mega-trend into a national, regional and global win-win solution with the support of modern process technology, and information and communication technology. The partnering arrangement would cause wealth to be shared on the basis of core competencies. It would raise productivity and create rather than lose jobs, while simultaneously addressing inequality. Growth in existing small, medium and large partner organisations would be stimulated, and so too the creation of new small and medium-sized enterprises. It must be kept in mind that small and medium-sized enterprises are responsible for between 60% and 70% of all jobs that are annually created in capitalist economies. The collaboratist business model embeds a virtual network of partners that constitutes a persistent innovation in technology that promotes the national, regional and global dissemination of ideas, as alluded to by Deutsche Bank. Moreover, in line with the contentions of Lagarde and Summers, it provides for behavioural and structural reforms; makes regional, national and global integration work for all stakeholders, including ordinary people; and it enables working people in terms of job security, education and home ownership. Cosequently the current authors believe that collaboratism will restore global trust in capitalism and repair the global economy.

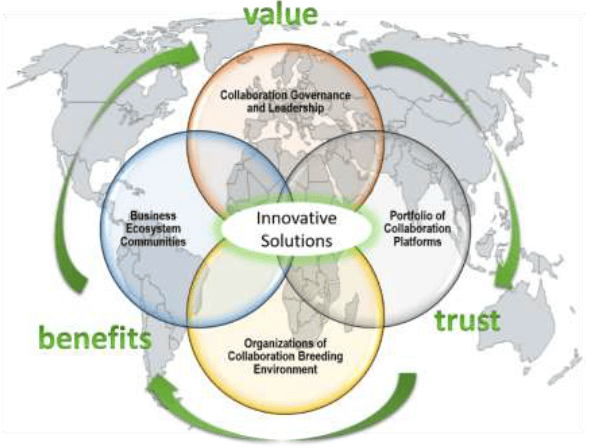

Figure 1 illustrates the application of the collaboration value space concept, which is characterised by value, trust and benefits of strategic importance (Semolic, 2012). Collaboratism is replacing the traditional hierarchical organisational structures with flexible, agile, collaboration-focused, process-based forms of organisational structures. Techno-entrepreneurship enriched by open innovation that is based on partnering and the utilisation of local, regional and global business sources that are empowered by overall society inclusions, is becoming increasingly prevalent. The partnering value proposition is based on a win-win philosophy to enable and foster competitive advantages for all stakeholders involved. Modern digitalisation and related enabling technologies provide endless opportunities for the introduction of different forms of virtual collaborative value chain business models.

Figure 1: The Open Business Collaboration Environment (Semolic, 2012).

Key interrelated components of the Open Business Collaboration Environment model

illustrated in Figure 1 are as follows:

- The participants can be profit or non-profit organisations, or a combination of the

two. - The business ecosystem communities can comprise of collaborating partners

from local, regional and/or international entities. - Portfolios of collaboration platforms and partner interests relate to, inter alia,

research and development, marketing and sales, manufacturing operations,

project work, and procurement. - Governance and leadership are of paramount importance. Collaborative

platforms are virtual organisations that need to be effectively and efficiently

integrated and co-ordinated by the principal partners applying state-of-the-art

programme management (Steyn & Semolic, 2016). - Governance of the portfolios of programmes in the virtual network of partners

must be led and managed by a Chief Portfolio Officer at the executive level of

the initiating partner organisation (Steyn, 2010).

Vincent van Gogh famously declared that “great things are done by a series of small things brought together”. Semolic (2012) contends that modern technologies have brought us opportunities to copy and use the logic of fundamental natural processes and systems and hence to use this logic to solve our daily business challenges. One such challenge is how to exploit the wealth and business opportunities of local, regional and global business potentials through partnering principles. Collaboration is becoming the “buzzword” in many industries. This applies to, inter alia: the automotive industry, where increasing collaboration is found between manufacturers, component providers and technology developers; virtual living laboratories organised by a group of ICT companies with a focus on co-development of new cloud computing services in support of collaborative open innovation ecosystems ; laser additive manufacturing and cognitive robotics technology collaborative platforms with the participation of local, regional and global collaborative partners.

Peltonieme and Vuori (2005) define a business ecosystem as a dynamic structure that consists of an interconnected population of organisations, which could be small and medium-sized enterprises, large corporations or public institutions, and other parties that may impact on it. The fact that businesses are an integral part of local, regional, interregional and global business ecosystems connected to specific industries, needs to be fully understood by business leaders and politicians alike. Politicians should shape harmonised local, regional, interregional and global business ecosystems standards, create opportunities for different forms of business partnering initiatives by minimising regulations, and provide adequate infrastructure for business services. In turn, entrepreneurs, business leaders and managers have the responsibility to create stakeholder value by providing key competencies embedded in their organisations or empowered by the products and services that they furnish when participating in the collaboratist virtual network of partners.

Finally, in the emerging knowledge-based economy, real intrinsic personal satisfaction becomes one of the critical success factors in any organisation. Inclusion, collaboration, co-ordination, integration, co-creation, customer satisfaction and win-win approaches emerge as key features of organisational culture. Competent, knowledge-rich and highly motivated people provide results and benefits that reach beyond stakeholder expectations.

Conclusion

Critics generally believe that globalisation, competitiveness and internationalism are firmly in retreat, and that the emerging protectionism does not augur well for the future. This is perceived as a reversal of the existing order, but an exception is the global dissemination of ideas that are powered by political freedom and assisted by innovations in technology. The current authors are of the opinion that the situation reflects to a large degree the inability of politicians and private-sector executives to cope with new challenges. The problems simply cannot be solved through adversarial political, economic and management practices. Politicians must harmonise all business ecosystems standards, and must create opportunities by minimising regulations and providing adequate infrastructure for business services. Entrepreneurs, business leaders and managers are responsible for creating stakeholder value by providing the key competencies when participating in the collaboratist virtual network of partners proposed by the current authors.

The current authors argue that for purposes of productivity, quality and competitiveness, modern organisations continuously need more sophisticated process technologies, as well as information and communication technologies that require higher-skilled workers. This supports the argument for extensive improvement in the quality and standard of education and training institutions, as well as the qualifications that they offer. Moreover, considering that the labour-cost advantage of establishing production facilities in other countries (such as China and Mexico, rather than locally) has shrunk considerably, it is clearly preferable to keep manufacturing assets where education and technological development are superior. Rapid technological development brings with it the need for structural and behavioural changes that not only cannot be reversed, but indeed have the ability to accelerate. Many critics maintain, however, that technological advancement has negative influences and effects that result in the loss of jobs. This is a view that the current authors reject.

Today’s organisations rely progressively more on knowledge workers and their innovation networks. Knowledge workers are increasingly the most valuable assets for sustaining business success. Current economies are dominated by “financial capital markets” that need to be transformed to the new concept of “knowledge capital markets”. “Knowledge capital markets” are based on collaboratism, championed by innovators and partners from innovative business ecosystems. The knowledge workers are the holders of explicit and tacit knowledge, are solution providers, and are the primary drivers of competitiveness and success. Moreover, to achieve a sustainable competitive edge, organisations must focus on their key competencies, and must develop organisational and technological excellence. For survival, modern organisations must increasingly participate in local, regional and international supply and value chains as partners.

The current authors’ proposed collaboratist business model of virtual networks of partners would lead to a sustainable boost in productivity, quality and competitiveness, requiring more sophisticated technologies and higher-skilled workers. It constitutes innovation in technology that promotes local, regional and global diffusion of ideas, and replaces the traditional hierarchical organisational structures with flexible, agile, collaboration-rich, process-based forms of organisational structures. Moreover, in support of the contentions of Lagarde and Summers, it provides for behavioural and structural reforms; it makes local, regional and global integration work for all stakeholders including ordinary people; and it secures jobs, education and home ownership for working people in mitigation of protectionism fears.

To satisfy the key competency needs and simultaneously to allay fears about protectionism, the current authors’ proposed collaboratist business model focuses on engaging local and regional partner organisations first, before moving into the international arena. Only upon failing to find competencies locally or regionally would the search be extended beyond national borders. In this manner, a modern form of “collaboratist globalism” is created that acts to mitigate the decline of globalisation that dominated economics and trade for decades. It will profoundly restore global trust in capitalism and repair the global economy.

Bibliography

Celente, G. 1998, “Trends – How to prepare for and profit from the changes of the 21st

Century”, Warner Books,

Cross, R. Rebele, R. and Grant, A. 2016, “Collaborative Overload”, Harvard Business

Review, Jan-Feb.

Geissbauer R. and Co. 2014, “Industry 4.0 – Opportunities and Challenges of the

Industrial Internet”, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC)

Levy, Rachael. 2016, “Goodbye Globalisation”, Business Insider, Australia, 14

November.

Pallot, Marc & Pawar S Kulwant, 2005, “Proceedings of the 1st AMI@Work

Communities Forum Day”

Peltonieme, M. and Vuori, E. 2005. “Business Ecosystem as the New Approach to

Complex Adaptive Business Environments”. Tempere University of Technology.

Semolic, Brane. 2012, “Global Knowledge Market and New Business Models”, PM

World Journal, Vol. I, Issue ILevy, RachaelI / September.

Steyn, Pieter & Semolic, Brane. 2016, “The Critical Role of Chief Portfolio Officer in

Governing a Network of Partner Organizations in the Emerging ‘Collaboratist

Economy’”. PMWorld Journal, Volume V, Issue 2, February.

Steyn, Pieter and Semolic, Brane. 2016, “Igniting the Economy”, The Project Manager,

Issue 29, South Africa, September.

Steyn, Pieter. July 2010, “The Need for a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO) in Organisations”,

PM World Today, July, Vol XII, Issue VII; Republished in the “Journal of Project,

Program, and Portfolio Management” University of Technology Sydney, Vol 1, No 1; The

Project and Program Management Journal”, Russia, October 2012.

World Economic Forum’s gathering in Davos Switzerland, 2017