An article by Professor Pieter Steyn, published in “Management Today” and “ProjectPro”, April 2001.

Introduction

Globalisation and the information age have impacted heavily on the way organisations are organised and managed. Superior strategic leadership has become an important competitive tool and is the basis on which leading organisations provide services or goods better than their competition can. Managing organisations through projects and programmes has become the integrative implementation link between corporate strategy, business strategy and operations strategy.

The holistic environment of the modern organisation

Both the internal environment of organisations and the external environment, in which they operate, have become much more volatile. Accelerated information flow which inspires change, requires that management decisions be made more frequently and more quickly. External to the organisation, the marketplace is likewise experiencing volatility. Changes in external environmental dimensions such as economic outlook, sociocultural issues, politics, ecology and technologies, also impact heavily on the way modern organisations are managed. Improved technologies probably have the greatest impact. This applies particularly in the area of Information Technology, motivating organisations to re-engineer their systems and business processes. This, in turn, requires that the knowledge, skills and behaviour of the human resources component in the organisation be continuously improved to maintain a competitive advantage, coupled with effective and efficient knowledge management.

According to Richard Lynch of Middlesex University, there are two types of change that impact on the organisation’s environment. Firstly, prescriptive change, which is brought about by a top-down strategic approach and formal control processes, and is the result of deliberate analysis and planning. Secondly, emergent change, which is triggered by unpredictable events in the external and internal environment of the organisation. These events are often unplanned or emanate from experiential learning inside the organisation, and are coupled with great uncertainty, requiring reactive and adaptive strategies that are negotiation-based, uncertainty-based and human-resource-based. (Lynch, 2000)

In light of the abovementioned issues, organisations can no longer rely solely on prescriptive strategies, such as profit maximisation, but have to rely progressively more on the emergent approaches to strategy development and implementation. Hence, in order to cope with the turbulence, sometimes even chaos, organisations are reverting to emergent approaches such as survival-based, uncertainty-based and human-resource-based theories and strategies. The last-mentioned category entails viewing human resources and their collective creativity as the most important assets of the organisation. According to Erik Schmikl, the world is now in the evolution of a chaordic business paradigm. (Schmikl, 2001). A chaordic system is an unstable combination of randomness and plan, infused by waves of change. The world environment is “emergent”, meaning that with the speed of change impacting on every organisation, the operational environment has dissolved into a series of events which frequently orchestrates chaos and confusion.

Traditional organisation forms and ways of managing organisations, are becoming obsolete. Rigid functional approaches to management can no longer cope with the demands of situations. Communication in traditional organisation forms is much too cumbersome, impeding the flow of information and managerial decision-making. Management in these organisations tends to lack both strategic purpose and customer focus. For project and programme management this has become a real challenge, since most of what has been assumed in the past century no longer befits current reality. Building on the platform of an accelerated technological revolution, the wave of innovation, entrepreneurial bioengineering and knowledge explosion, all of society now has to cope with the information revolution and globalisation of the economy. Human creativity within teams is becoming increasingly important within the context of the emergent and virtual team-management environment. Managers are entering more and more into a culture of risk, in that business outcomes are predictable only in the short term. Having to lead and manage in this new emergent culture of risk and uncertainty, organisational structures and management are compelled to undergo more radical changes than at any time in the past. Moreover, these new structures need to be highly flexible.

Management through projects and programmes

The new general management paradigm/approach

Managing organisations through projects or through project-portfolios (also known as programmes) is gaining popularity, since it is a management approach that integrates and coordinates current chaotic strategic business and operational dimensions. It is an approach which effectively and efficiently utilises the Total Quality Management principles of having a customer focus, involving management and employees at all levels of the organisation in team work, decentralising managerial decision-making, focusing on continuously improving the products, services, systems and processes of the organisation, and creating a learning organisation that stimulates human creativity and knowledge management.

At the heart of the project and programme management approach, is creating high-performance integrated project teams that operate in a coordinated manner across functional boundaries within the organisation. Specialist outsourced teams which enhance the organisation’s capacity, are integrated into high-performance project teams. The actions and performance of the teams are coordinated and integrated by a project manager, who maintains a continuous focus on the customer’s needs, irrespective of whether it is an external or internal customer. Moreover, the project and programme managers ensure that the goals and objectives of the project deliverables are aligned, and remain aligned, with the strategic objectives of the organisation.

Generating projects, as described above, leads to the creation of portfolios of projects within the organisation. These must all be aligned with the strategic objectives of the organisation. This calls for a higher level of management, i.e. to manage portfolios of projects within the organisation (also known as programme management).

The programme or project-portfolio manager has the task of aligning the outcomes of each project with the strategic intent of the organisation, prioritising the projects in the portfolio in order of importance, and ensuring that suitable resources are available for each project in designated time periods.

An appropriate definition for programme management is as follows: “The coordinated and integrated management of a portfolio of projects and unique tasks that brings about change and transformation in organisations to achieve benefits of strategic importance.” The benefits of strategic importance are tangible or intangible, and may include improved productivity, customer service, competitiveness in the marketplace, market perceptions, business processes, shareholders’ value, and higher quality products and services. The organisation’s benefits need to be properly managed by continuously monitoring the projected benefits, measuring actual benefits versus the projections, providing feedback to all stakeholders on progress, and making quick response adjustments where change is necessary.

Projects and large tasks are unique assignments that cannot be undertaken by just one department. According to Wijnen and Kor, two Dutch researchers, these cannot be undertaken using existing standard procedures or improvisation. The result is that organisations have to adopt management through projects and programmes that effectively and efficiently provides the required framework. (Wijnen and Kor, 2000).

To distinguish between projects and programmes, one could consider the following explanations proposed by Wijnen and Kor (2000). Projects concentrate on realising a single predetermined result, whereas programmes strive for the achievement of a number of goals that are sometimes conflicting. The project approach directs energy, while the programme approach combines energy. Therefore, according to Wijnen and Kor, management emphasis in projects is on defining the final outcome, whilst in programme management the emphasis is on establishing which activities are essential for the achievement of the organisational goals and objectives.

Key success factors exist for both project and programme management. Before commencing, it is essential that outcomes and objectives are properly defined. These outcomes and objectives must be communicated to all stakeholders. Moreover, all projects, initiatives and tasks must be properly prioritised by top management. Management must also assign appropriate authority, responsibility and accountability to various stakeholders. In this regard, the programme and project managers must be given full authority over project work.

The programme approach differs from large projects because of its total goal-oriented focus rather than prescriptive outcomes. Activities in a programme often originate from the bottom up, arising from work in which the various project teams are engaged. These activities are often created through innovative ideas that emerge from the learning organisation ranks. However, activities in programmes also originate at the top managerial level to create fundamental organisational change and transformation as a result of prescriptive and emergent strategy development.

At this point it would be appropriate to look at some important elements of the programme approach. Firstly, goals must be clearly specified and the actions to achieve these goals must be itemised and prioritised. This should be followed by assessing the organisational and financial effects of the formulated action. A crucial mistake which is often made is that management does not pay enough attention to the resources required to achieve these goals within a specified time frame. This leads to project or programme failure, since these often have to be terminated during implementation due to a dearth of resources.

In the strategic and innovative programme approach, substantial flexibility is required in goals so as to cater for unexpected changes in the external and internal environment of the organisation, as discussed earlier. These changes could be as a result of political, socio-economic, economic or technological factors, as well as conditions in the marketplace, or unexpected resource constraints. The project- portfolio within the programme must be based on the strategic or innovative goals and ultimate objectives of the organisation. In the programme approach, these goals are then pursued to achieve the organisational objectives to a satisfactory degree, since it is often impossible to achieve the goals exactly as initially envisaged.

Wijnen and Kor (2000) propose the following general criteria for managing strategic and innovative programmes:

- The tempo criterion, which gives priority to those actions that will speed up the implementation process.

- The feasibility criterion, which supports those activities that increase the probability of programme success. A typical example is new technology which will enhance value whilst complying with the cost-benefit analysis principle.

- The efficiency criterion, which compares financial or quality values of alternative activities, selecting the most beneficial ones.

- The flexibility criterion, which is emergent in nature and determines the extent to which activities can be changed during the life-cycle of the project or programme. The flexibility criterion also determines the ease with which capacity can be switched from one activity to another, as the emergent situation may require.

- Finally, the goal-orientation criterion, which assesses the relevance of all the activities in the programme to the goals. The goal-orientation criterion determines that highest priority be given to those activities making the greatest contribution to the formulated programme goals.

David Partington of the Cranfield School of Management states that to cope with modern change, managers have to “blend agility with direction, creativity with control, and flexibility with structure”. (Partington, 2000). This means that the rate of change of pace now requires high levels of coordination and integration of strategy implementation, which can be achieved only through effective and efficient programme management. He deplores the fact that strategy literature concentrates on theories about how best to formulate and plan strategy, while at the same time underestimating the difficulty of developing and implementing strategy at the corporate, business and operational levels.

Partington (2000) contends that organisational change and transformation can best be achieved through the management of programmes and projects. Maximum flexibility and control are provided by the progress reviews adopted in the management-through-programmes approach. Its team-based structures are multifunctional and cater for authority, responsibility, accountability, expertise, quick response and cooperation. Moreover, its structured approach to change allows for the acquisition and diffusion of knowledge in true learning organisation spirit, while its skills are relevant to strategic change programmes. When analysing the problems of strategy development and implementation, the need for programme management becomes obvious. Corporate missions and objectives are set by executives who then arbitrarily leave implementation to functional managers. A further problem is that existing cultures and systems in the organisation are totally incapable of changing themselves and thus require change strategy interventions. As a result, strategic intentions become diluted and compromised, and are eventually postponed, often indefinitely.

Unstructured approaches to strategy development and implementation, coupled with contradictory directives that create resistance to change, also lead to failure of implementation. Partington alludes to the fact that a properly coordinated programme approach enables change to be managed outside the constraining norms and processes of existing culture. This view is supported by the current author’s practical experience in South African organisations where strategic transformation and change were guided by a formal management-through-projects/programmes approach. In all situations, both in public and private organisations, an independent programme office was established. This office, then, managed the strategic planning (formulation), development and implementation processes. Project Teams were created from inside and outside the organisation (outsourced teams), which delivered the goals and objectives of the programme outside the constraints of the existing organisational culture, with great success. Nevertheless, it is not suggested that this approach is entirely free from resistance to change. Rather, the structured approach, when managed properly, creates a driving force that positively dilutes pockets of resistance. As the resistance to change dilutes, transformation of the organisation accelerates towards achieving the strategic goals and objectives of the programme.

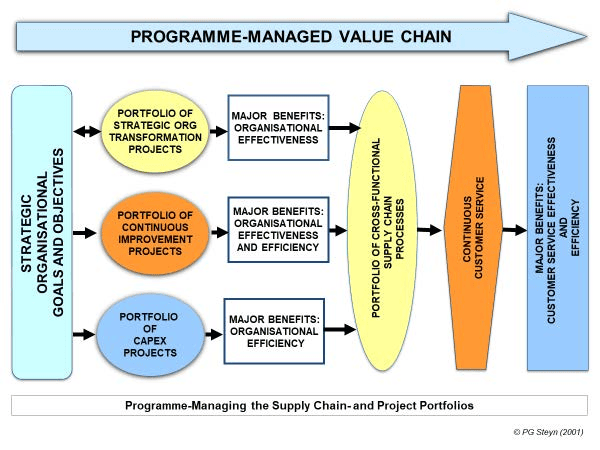

In their research, Murray-Webster and Thiry (2000) conclude that programme management provides an integrative framework through a collection of change actions (projects and operations) which are purposefully grouped together to provide a vehicle to ensure that strategy is implemented. Through investigating how organisations shape their programmes, many researchers and consultants, including Murray-Webster and Thiry, indicate three ways in which organisations shape their programmes. These are capital expenditure (capex) programmes, strategic or goal-oriented (transformation and change) programmes, and innovative (continuous improvement) programmes.

Capital expenditure project-portfolio programmes are highly prescriptive or specified and are grouped around common themes such as a business unit, specific groups of resources, or knowledge areas (Murray-Webster and Thiry, 2000). Their benefits include better prioritisation of and control over multiple projects, better allocation and utilisation of resources, and appropriate identification and management of dependencies between projects. The main advantage of the capital expenditure programme approach is improved organisational efficiency.

Strategic or goal-oriented programmes come about as a result of the planning, development and implementation of both prescriptive and emergent strategies. Strategic programmes are grouped around a common aim or purpose, such as a strategic objective where uncertainty exists about the final outcome, strategic scope changes occur, and projects and large tasks are added or removed accordingly (Murray-Webster and Thiry, 2000). Benefits derived from this approach includes that: strategic needs are translated into tangible actions, there is efficient absorption of emergent change, uncertainty is reduced through iterative programme development, and finally, projects are subject to an integrated review and approval process. The main gain achieved through the strategic programme approach is organisational effectiveness.

Innovative (continuous improvement) programmes can be prescriptive or emergent and are grouped around a common platform, such as a process, business system or infrastructure that needs continuous enhancement (Murray-Webster and Thiry, 2000). The benefits that could be derived from this approach are vast. Firstly, innovative bottom-up initiative can be effectively channeled. Moreover, multiple initiatives are grouped to create actions that are coherent and efficient, while short-term actions can be fitted into a longer-term strategy. Assessment of the derived advantages can, with clear perspective, be made within an organisation. The innovative programme approach has the advantage that it leads to the coordination and integration of continuous improvement initiatives across the whole organisation. The main gains are organisational effectiveness and efficiency.

The author asserts that, as illustrated in Figure 1, a fourth initiative in the management-through-programmes approach can be added to the above, namely the supply-chain portfolio that is also programme-managed cross-functionally. Processes in the supply chain are project and normal operational in character and focus on improved customer service. For this reason, these programmes are generally grouped around customer-service initiatives pertaining to operational process, infrastructural support in the organization and the different market segments within which the organisation operates.

Major benefits derived from this approach include efficient coordination of multiple customer-service initiatives, and effective integration and coordination of a customer focus between market segments. The main gains are organisational effectiveness and efficiency in respect of customer service. A major difference in this initiative is that the management-through-programmes approach coordinates and integrates predominantly operations activities in continuous processes, but it must be kept in mind that the supply chain product development process and processes for project work serving external customers are project driven.

It is submitted that the four programme configurations discussed above, are not mutually exclusive. They support each other integratively in the organistional environment and have the further advantage that the organisation’s strategic vision and mission are systemically linked to the operations activities in an effective and efficient manner. Moreover, it is important to note that the four programme configurations can be applied effectively to both public and private sector organisations.

Top management support is essential

The management-through-projects-and-programmes approach requires extensive support from top management in order to be successful. Unfortunately, persons in top management, through their actions, often play a role in project and programme failure. The following are some of the reasons: (Dugan, Thamhain & Wilemon, 1977; Jiang, Klein & Balloun, 1996; Ward, 2000; Burkhard, 2000).

- Not providing accurate and firm information to project and programme managers.

- Being too optimistic regarding potential strategic and operational benefits that can be derived from projects initiated by them.

- Making the mistake of massaging business proposal feasibilities to ensure that their projects would proceed.

- Poor prioritisation of projects.

- Underestimating organisation resources, infrastructure and process capabilities for project/programme support.

- Mismatching budget expectations and actual project costs.

- Functional managers often being trapped in “silositis”, hence being unable to see the holistic integrative system.

- Top management reducing the project or programme scope to fit the initial budget, but then proceeding with undisciplined upward variations during project implementation. These variations are often not properly authorised or funded.

- The inability of top management to create a trust, support and cohesion culture, which is so important for relational management and creating positive perceptions that motivate team members.

- Top management’s pushing for unrealistic time frames to complete projects, impeding conceptualisation and sowing the seeds of failure.

- Arbitrary introduction of methodologies in the belief that it would solve a dearth of management acumen.

- Indiscriminate switching of resources between projects and programmes.

Conclusion

The “new economy” situation demands a fresh approach to managing organisations. Human leadership skills, such as communication, negotiation, motivation, facilitation, conflict resolution, and even counseling, are now more important than ever before. Traditional organisations are now realising that in order to be competitive they are compelled to improve their leadership skills. Hence, organisations are motivated to revert to the management-through-projects-and-programmes approach, where the organisation is rearranged into a portfolio of “small businesses” where project and programme managers execute tasks much more effectively and efficiently.

New sets of knowledge, skills, values and behaviour are required to cope with the new management paradigm. Organisations are required to become learning organisations that continuously enhance the knowledge, skills and experience of their human resources, including top management. To be successful in a management-through-projects-and-programmes approach requires maximum support from top management. Managers at all levels of the organisation must recognise the importance of creating a culture of trust, in which innovation and cohesion are allowed to flourish. This, in turn, will create positive perceptions about management, leading to capable and well-motivated team members who strive willingly and enthusiastically to achieve the mission and objectives of the organisation.

© Professor Pieter Steyn

Principal, Cranefield College of Project and Programme Management

REFERENCES:

- Burkhard, Rudolph, “Good People, Bad Habits”, proceedings of the 15th IPMA World Congress, London, May 2000.

- Dugan H, Thamhain H, and Wilemon D, “Managing Change in Project Management”, proceedings of the 9th annual International Seminar/Symposium on Project Management, The Project Management Institute, 1977.

- Jiang J, Klein G and Balloun J, “Ranking of system implementation success factors”, Project Management Journal, December 1996.

- Lynch, Richard, “Corporate Strategy” 2nd Edition, Pitman Publishing, London, 2000.

- Murray-Webster R and Thiry M, Gower Handbook of Project Management, 3rd Edition, Chapter 3, “Managing Programmes of Projects”, Gower publishing, England, 2000, Ed. Rodney Turner.

- Partington, David, Gower Handbook of Project Management, 3rd Edition, Chapter 2, “Implementing Strategy through Programmes of Projects”, Gower Publishing, England, 2000, Ed. Rodney Turner.

- Schmikl, Erik, Cranefield College of Project & Programme Management, Module M4 ”Integrated Corporate Strategy” learning material, 2001.

- Steyn, Pieter, Cranefield College of Project & Programme Management, Module M2 “Strategic Project and Programme Leadership” learning material, 2001.

- Ward, Garth, “Disconnected Project Management”, proceedings of the 15th IPMA World Congress, London, May 2000.

- Wijnen G and Kor R, “Managing Unique Assignments, a team approach to projects and programmes”, Gower Publishing, England, 2000.